The monorail station remains brilliant. Just avert your eyes from all the recent changes to the Seattle Center. Dream instead of bubble elevators and fun fairs.

-

-

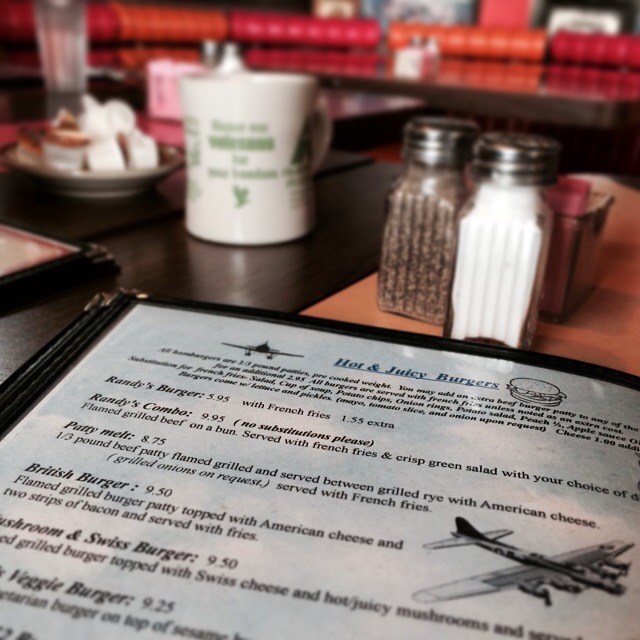

One of my favorite places in the world: Randy’s Restaurant on East Marginal Way in Tukwila Washington. My grandma brought me here at some point in the 1970’s, and I come back whenever I can get a ride.

-

-

-

-

The ferry ride from Seattle to Bainbridge Island

-

Regular readers might wonder where I’ve been these past few years. Summary: I was the CEO of a technology start-up. My stated objective was to lead the organization through the start-up phase, then to identify, negotiate, and complete a merger deal.

The motto of the company was “Proof for the Masses” and I was determined to make sure we achieved that goal. Result? To quote the Telegraph: “Facebook Buys UK Startup Monoidics.”

The company:

The team:

The day we pitched the sale at Facebook HQ in Silicon Valley:

Lots more information can be found:

Allthingsd: Facebook Acquires U.K. Software Startup Monoidics

PC Mag: Facebook Buys Bug-Zapping U.K. Firm Monoidics

Telegraph: Facebook buys UK startup Monoidics

Information Age: And so, Silicon Valley slurps Tech City’s brightest minds

Computer World: Facebook lands bug hunters with Monoidics buy

-

My mother came to visit for her sixtieth birthday, and I was thrilled beyond belief to buy her a first class ticket.

If I could make her entire life match the delights of the British Airways business lounge, I would. My mother is heroic beyond all understanding. I wish that I could write a tribute that conveyed her wit, her vibrance, her courage – but words are too limited to describe her brilliance.

My mother is an absolutely astonishing person, and she deserves any and all treats that can be organised. This time that translated to plays, palaces, museums, and lots of time with her scandalous grandchildren. They love her, and miss her.

My mother is also, of course, my mother – a job that never ends. She still tells me when daylight savings happens, and writes to ask if I’m taking my medicine properly. She has wasted thirty years in a futile attempt to get me to wear a hat, staunchly insisting that I do not look stupid even in the most extreme versions:

-

Ten years ago I lived and worked in Portland Oregon, and rarely ventured more than twenty blocks from the house I had rescued from dereliction. I had a family, community, and career, all anchored by the geography of a friendly small river city.

I was grounded, literally, in that place and time – to the extent that I never once drove my rackety Volvo 240 up on to the freeway overpass intersecting the neighbourhood. The only significant irritation was the fact that passerby often expressed the view that I was too young for the responsibilities I had assumed. It was a good life, tidy and correct, and it looked exactly how you might expect it to look.

But as my thirtieth birthday approached I started to wonder – is this it? I had worked so hard to drag my small family out of poverty, to give my children the life they deserved, protected from violence and insanity. But normality is so…. normal.

I knew artists and musicians, had plenty of stimulating and eccentric friends. But our range of experience started and ended within a mile of Interstate 5. The thin corridor of Seattle, Portland, Olympia, San Francisco: it was all the same as far as I could tell. It was the where, how, who, why, and what of life. It felt comfortable. I didn’t want to feel comfortable.

Lots of people have midlife crises. I reckoned I was not eligible, because my residency on earth is restricted – there was simply not enough time to fret and fiddle. I didn’t want to make minor changes, switch neighbourhood, partner, car, or job. None of that would have been sufficient, because I was never particularly interested in any of those things.

I had already survived two different kinds of cancer, worked my way out of poverty, changed my social class, married and divorced, raised kids, gone to graduate school, started and abandoned careers, flirted with fame and fortune. I was always reckless and restless. Transgressive change has a different meaning when you are born and raised in chaos.

I didn’t want to leave the Northwest, didn’t intend to change anything at all. But one day it just happened, for no discernible reason. I woke up one morning, much as any other day, except for a single small detail: I knew I would leave.

Not just the place but the life. The music and madness of the NW, the rugged individualism and bootsrap mythology of the West. The totality of my upbringing and background. Not because it was lacking, not because I was unhappy, but instead simply because I wanted to go. I had spent three decades vigilantly seeking security, and then I decided that I wanted something else, something intangible, away, different, new.

Life is about departure; we’re all dying, fast or slow. The question is how we spend the time we are allotted. And time, make no mistake, is a commodity.

Before my thirtieth birthday I had never been east of the Rockies. Since then I’ve been to Paris, Rome, Venice, Barcelona, Lisbon, Helsinki, and too many other places to describe or remember. I’ve criss-crossed most of the United States on book tours, telling funny stories that make audiences cry. I’ve visited the great museums of the world, and learned more than I care to know about the ghettos.

I’ve lived in ancient university towns, staunchly defending my working class antecedents in the face of intellectual pomposity. I’ve been the owner and captain of a canal boat, traversing narrow waterways and difficult locks without appropriate credentials or any discernible skills.

I’ve been poor and stranded, and I’ve been wealthy and free. I’ve lived off the grid, and I’ve been the CEO of a high tech company. I’ve been an immigrant, an American expat, and a British citizen. I’ve been enraged over a third inexplicable cancer diagnosis. I’ve enjoyed the company of my strange children, watched with bemusement as they launched their own eclectic and turbulent grown-up lives.

I have also failed utterly to figure out where I belong in this world, principally because I do not belong anywhere. I could say that my early life was parochial, provincial, anti-intellectual; the observation would be true. But the same could be said of Cambridge, Oxford, and the hipster culture of East London, depending on your point of view. And that is fine – the people who choose to live in these places presumably like what they’ve found.

The truth is that you can ruin your life, or venture upon on a fantastic odyssey, wherever you happen to be. Some people like to stay home, enjoy familiar routines and scenes. I love crowds, strangers, disorder. I want to keep moving. I want to see more.

My life might have been just as rewarding if I had never left home: it is impossible to say. My kids would have grown up no matter where we lived. The cancer would have been discovered, regardless of my address. But if I lived in Portland I wouldn’t have access to hourly train service to Paris. If I had chosen Seattle or San Francisco I would not have been able to spend random weekends in Rome.

If I lived in the states I would not decide to winter in the south of France on a whim – or have the giddy thrill of typing that sentence. I wouldn’t have written this journal, and I would not have met the multitudes of people I have encountered along the way.

I was born and raised in the Pacific Northwest and planned to stay there forever. Now I live in England and my primary topic of conversation is: where should I go next?

Ten years ago I started this journal with the declaration this is the start of the adventure – and it hasn’t ended yet.

-

Over the course of this peripatetic existence there have been more than two dozen occasions when people have declared their undying (and hopeless) love for me; six proposals of marriage; four people I’ve liked enough to split the rent; two I’ve married; one person sufficiently persistent to know longer than a year or two. Throughout all of these machinations and maneuvers I have remained puzzled by the emotions, drama, betrayals, reversals. I’ve had more than my statistical share of romance, and neither enjoyed nor believed in the experience. This is what I think of romantic love: shrug. Whatever.

I reckon that what most people call love is just infatuation, a fleeting and fundamentally biological feeling. I don’t do feelings. They’re not reliable, logical, or trustworthy. The main proof of this is the fact that when I reject advances or break up with people they never remain friends. Perhaps this is normal: I wouldn’t know.

It is however a cheat. If I like someone, it is forever – regardless of whether they live up to my expectations or give me exactly what I want. When people say they love me, I have always asked “why?” or some variation of “uh-huh, but for how long?” – invariably valid questions, if not exactly endearing.

It is not surprising that I cannot even remember the faces of the people who claimed to love me when they merely wanted me to love them. First husband, what was his name again? I cannot recall, and I am not exaggerating. My imperative truthfulness is a scourge, and ordinary humans prefer marriages based on mutual admiration. In my life friendship has always been more important than romantic love, friendship is based on realistic expectations, and my only lasting romantic relationship has been with my best friend, the person who has been there year after year, through every adventure, no matter how strange or alarming. Lots of people have claimed to love me. But there is only one person around when I need a ride to the hospital, who also wanted to help raise my kids, who can be relied on to say yes when the rest of the world says no.

Friendship is fundamental, rewarding, heartbreaking, real. My friends are the people who show up when I need them and stay away when I am too ragged to talk. They’re the people who laugh at my grotesque stories, understand my flaws and hesitations, and show their own. They’re the people who wander away, but always come back.

There are thousands of people I call friend, and only a handful of people I talk to with any consistency. I have too many responsibilities, too little time, and an urgent need to see more of this world before I depart.

The last few months have been difficult, a fact that I would never have admitted as the events unfurled. I’ve hidden myself away, closing up around the pain and confusion, saying I’m fine, it will all be fine. But spring is arriving and it is time to get back to work.

I am humbled by the extraordinary opportunities I’ve had, and by the people I met along the way. I don’t say it enough, and I want to make this clear: I love my friends, and thank them with all sincerity. Not for what they’ve done, but instead, for who they are.